CAMP ONAWAY CENTENNIAL HISTORY BOOK

“I started writing this history in the summer of 2000, after many months of collecting the necessary written and oral information. The early part of this history was compiled from old brochures, camp “logs”, letters, diaries, photographs, interviews with campers from the 1920s and 1930s, (some very good oral history interviews were done in the 1980s when the idea of an Onaway history first came into being), with particular gratitude for the written historical and personal memories of Henry Hollister about his mother’s time as Director. For the later years Trustee Minutes and correspondence, the Onaway Circle Newsletter, Director Sermons and summer and winter reports, some counselor binders of summer schedules and activities, the C.O.D. Notebooks, Song Books, Birch Bark Box contributions, have added greatly appreciated information.“

Helen refers to the book as a backpack of memories and invites all curious readers to join her on a journey rich with stories, artifacts and many, many wonderful photographs.

Purchase the book

To purchase the book, a delightful read for anyone who ever attended a summer camp, contact the office or print and send us this order form.

The following is an excerpt from a draft of the book:

The Summer of 1912

On July 12, 1912, the stage coach stopped at the foot of the Onaway driveway and discharged six young ladies, the first Onaway campers. The Hollister family was represented by the sisters Katherine and Tertia Park, Mrs. Hollister’s nieces. The other four campers were Marion Manson, Marcia Chapin, Lillian Crane and Katherine Green. A few days later another young woman, Frances Frost, aged 27, who had watched the arrival of the stage from Mrs. Nutting’s Boarding House across the road, walked down the driveway and found Onaway life so delightful that she stayed on as a counselor in 1912, was Head Counselor by 1915, Assistant Director by 1925, and Director from 1937 to 1943.

That first summer everyone (including the Hollister family and the counselors) slept in the original livestock barn and chicken coop, named “Perches”.

They then lined up to greet Mrs. Hollister at the door of the dining porch, where each one was asked if she had brushed her teeth and cleaned her nails. Given the icy nature of the pump water, the complications of dress, and the difficulties of spitting into the slop pail, this inspection may have been more necessary to general well being than we can appreciate today. In any event, this “Teeth and Nails Inspection” became one of the first of many Onaway traditions created by Mrs. Hollister which continue to this day. For many years Mrs. Hollister awarded a cup at the end of camp for the best record in this particular daily ritual.

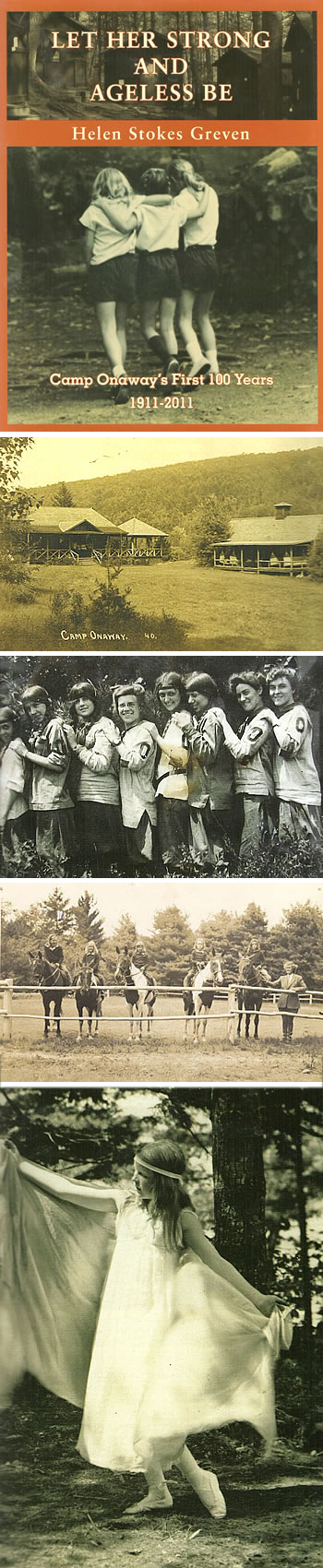

The routine of the day (after a bugle call) began with “aesthetic dancing”. Mrs. Hollister was convinced that the girls would be grateful in later life (if not in the moment) for this training in grace and poise. She instituted a little dance pageant at the end of the summer, depicting such tales as Hansel and Gretyl, or Snow White, taking great care to rearrange the plots so that all the characters were lovable in the end. The costumes were dyed cheese cloth (each camper had to bring 5 yards of cheese cloth to camp), draped gracefully, unless the wind happened to blow in the wrong direction. Dance was followed by Crafts, or the making of little purses, or bookmarks, or Camp Onaway headbands, to be worn Indian style. When the bugle blew all campers went “bathing” at the beach. Mrs. Hollister watched over the campers in their bloomers, blouses and stockings from the one rowboat, fully dressed in a long crepe de chine skirt, middy blouse, tie, with glasses and whistle around her neck. Campers could not be in the water unless Mrs. Hollister was in her rowboat. It is not known if Mrs. Hollister could actually swim, but she made sure that all her campers learned to swim, no small achievement for Martha Pattison (who also taught aesthetic dancing) in 1912 when ladies were not expected to know how to swim. This was the beginning of another Onaway tradition – excellence at the waterfront.

Swimming was followed by lunch, prepared by the Hollister’s cook from Rutherford New Jersey who had accompanied the family to camp. Meals were excellent, but the purchase and refrigeration of food was an on-going challenge. The ice house figured prominently. On one side of the ice house was a walk in cooler where hanging slabs of bacon, ham, beef, fresh fruits and vegetables could be kept in good condition for long periods of time. The rest of the building was used to store huge blocks of ice cut from the lake and taken by horse drawn sledge to the icehouse and packed in sawdust the previous winter. Much of the produce came from the Russell Farm, on the way to Hebron. Mr. Russell also delivered milk from his cows to Onaway in his horse drawn buckboard daily, and took Onaway’s garbage back for his pigs. Other local farmers provided butchered lambs, cows, chickens, ducks, eggs and vegetables. What could not be procured locally was shipped from Boston to Bristol on the Boston and Maine Railroad, packed in ice in large wicker baskets; or in the case of the preserves, jams, nuts and jellies from S.S. Pierce and Co. in excelsior in large wooden barrels. These baskets and barrels would be taken from the train station to Onaway by the mail stage. If goods were needed from Plymouth, Mrs. Hollister had to go herself in a horse and buggy driven by Mr. Smith of the Hillside Inn. Mr. Smith then took Mrs. Hollister’s purchases back to Onaway in his large dump cart drawn by his team of Clydesdales. It took an entire day for Mrs. Hollister to go 20 miles on a road deep in either dust or mud, and she only made this trip two or three times a summer.

She must have looked with disfavor on girls who complained about the food! Every day a small amount of candy was served to each girl at the end of lunch – the beginning of another long appreciated Onaway tradition.

After a “rest hour” (and another bugle call) the girls reassembled for the afternoon’s sports activities. This could include tennis on the one grass (recently weeded) tennis court, croquet on the adjoining field which sloped about 15 degrees and had many hidden rocks, or basketball and baseball on another part of the field which yielded delicious blackberries in season.

Sometimes there were hikes. A typical hike started with the girls marching two by two north on the Mayhew Turnpike. For this part of the hike the girls had to wear heavy brown skirts which reached to the ground and covered their bloomers. After a stop at the East Hebron Post Office for water and cookies from Mrs. McClure, they hiked up the nearby logging road where they hid their skirts in the bushes before climbing the “mountain” through heavy brush and towering trees. They arrived back in camp in skirts, as befitted Onaway ladies, and we will never know whether Mrs. Hollister knew of the hidden skirts, since neither she or Miss Frost ever went on these hikes.

After perhaps another swim, the girls had supper, then gathered in the newly named “Woodland Hall” for games, charades, singing, and dancing together to records on the victrola. Once again Mrs. Hollister made sure that the music selections were appropriate for well brought up young ladies. If the weather cooperated everyone went to “Campfire Rock” for the sunset and the goodnight circle.

Conditions of life at Onaway in 1912 could not have been easy for girls accustomed to a gentle and protected upbringing in modest luxury. Mrs. Hollister wanted to save these girls from summers of languishing on verandas, and offer them opportunities to learn who they really were underneath their corsets, and rigid social expectations. In 1912 this was a very brave and radical idea, and I am really in awe of all the girls and women who contributed to the unqualified success of that first summer. What a base they created for the next 100 years to build upon!